Franklin Flores

Franklin Flores | |

|---|---|

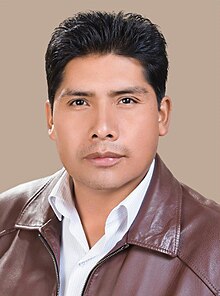

Official portrait, 2019 | |

| General Manager of the Food Production Support Enterprise | |

| Assumed office 26 May 2021 | |

| President | Luis Arce |

| Minister | Néstor Huanca |

| Preceded by | Marvin Pereira |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies from La Paz circumscription 18 | |

| In office 18 January 2015 – 3 November 2020 | |

| Substitute | Asunta Quispe |

| Preceded by | Martín Quispe[α] |

| Succeeded by | Basilia Rojas |

| Constituency | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Franklin Richar Flores Córdova 8 July 1979 Aisacollo, La Paz, Bolivia |

| Political party | Movement for Socialism |

| Alma mater | Higher University of San Andrés |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature |  |

Franklin Richar Flores Córdova (born 8 July 1979) is a Bolivian politician, trade unionist, and former student leader serving as general manager of the Food Production Support Enterprise since 2021. A member of the Movement for Socialism, he previously served as a member of the Chamber of Deputies from La Paz, representing circumscription 18 from 2015 to 2020. Before that, he served as a Sica Sica municipal councillor from 2010 to 2014, during which time he held office as the body's president. In 2021, Flores was his party's candidate for governor of La Paz, placing second in that year's gubernatorial election.

Early life and career

[edit]An ethnic Aymara, Franklin Flores was born on 8 July 1979 in the Sica Sica Municipality of La Paz. He completed primary studies at a small rural school in the Aisacollo community, graduating high school in Konani before moving to La Paz in 1997, where he attended the city's American Institute.[1] Flores studied law at the Higher University of San Andrés (UMSA), though it is unclear whether he completed his degree.[2] During his time at the university, Flores rose through the ranks of students' union leadership, serving as executive secretary of the UMSA Faculty of Law Student Center. Returning to Sica Sica, he became active in various trade union organizations in and around the Aroma Province.[3]

Flores's union activity led him to join the ranks of the ruling Movement for Socialism (MAS-IPSP), a party with which he sought his first elective position. In the 2010 municipal elections, Flores headed the MAS's electoral list of councillors in the Sica Sica Municipality, winning the seat for the party. Throughout his term, Flores served as president of the Sica Sica Municipal Council, attaining the support of the legislature's MAS majority to hold the post five consecutive times between 2010 and 2014.[3]

Chamber of Deputies

[edit]Election

[edit]Nearing the end of his term, Flores resigned from office to run for a seat in the Chamber of Deputies. The MAS postulated him in the rural circumscription 18, a constituency encompassing the Aroma, Loayza, and Villarroel provinces, as well as segments of Murillo Province.[3] During the campaign, Flores was involved in a minor scandal after the municipal vehicle he was driving collided at high speeds with a white minibus, leaving four injured, including himself. Following the accident, Flores allegedly abandoned the van, leaving his unlicensed nephew as the driver.[4] Despite the incident, Flores went on to win the election with 84.60 percent of the vote.[5] The landslide victory, according to sociologist Salvador Romero, owed to the MAS's overwhelmingly hegemonic position in the rural highlands, where "parliamentary campaigns are symbolic" and victory is assured "regardless of the candidates nominated".[3]

Tenure

[edit]During his tenure in the Chamber of Deputies, Flores established himself as a close ally of President Evo Morales, the ruling party's top leader.[2] When Morales controversially presented his resignation in 2019, Flores led the bloc of Morales loyalists that sought to reject its approval in the Legislative Assembly. Amid shouts and protests, Flores attempted to present a motion of prior consideration in a bid to stall a vote on the topic. However, he failed to gain the legally necessary support of five other legislators to pass the motion. Morales's resignation was formally approved on 21 January 2020—two months after he had already left office—by a majority of those present, including a majority of the MAS caucus.[6][7] Arguments between opposing MAS legislators continued after the session, with Flores accusing Senator Omar Aguilar of manipulating the vote count.[8][9]

Commission assignments

[edit]- Plural Justice, Prosecutor's Office, and Legal Defense of the State Commission

- Ordinary Jurisdiction and Magistracy Council Committee (2015–2016)[10]

- Constitution, Legislation, and Electoral System Commission

- Constitutional Development and Legislation Committee (2016–2017)[11]

- Government, Defense, and Armed Forces Commission (President: 2017–2018)[12]

- Plural Economy, Production, and Industry Commission (President: 2018–2019)[13]

- Education and Health Commission (President: 2019–2020)[14]

La Paz gubernatorial campaign

[edit]Shortly after the conclusion of his term in the Legislative Assembly, Flores profiled himself as a contender for the La Paz governorship. In early November, several agrarian workers' unions in Flores's home province of Aroma proclaimed him as their pre-candidate for the MAS's nomination, a position officialized thanks to the support of the Túpac Katari Peasant Federation.[15] From then on, Flores quickly established himself as the favorite to win the internal primary, facing only one other pre-candidate, Beimar Calep Mamani, the outgoing mayor of Palos Blancos.[16][17] His position as the MAS's gubernatorial nominee was made official on 27 December, with Morales stating that he had been chosen "almost by consensus".[18][19] This claim faced pushback by sectors supporting Mamani, leading Página Siete to later describe Flores as having been "chosen by Evo", an allegation he denied, pointing out that over 2,000 local communities had backed him before he won Morales's endorsement.[1][20]

Throughout the campaign season, Flores enjoyed a slight lead in opinion polling, a fact aided by the death of Felipe Quispe—the original frontrunner—midway through the race.[21][22] By election night, exit polling conducted by Ciesmori and Focaliza indicated that Flores had attained nearly forty percent of the vote, an over ten-point lead above his closest competitor.[23] The margin was substantial enough for Red UNO to call the race for Flores, believing that with the remaining votes, he would be able to circumvent a runoff.[24][β] With that, Flores declared victory.[25] However, as the race narrowed, the final count ultimately gave him 39.7 percent of the vote, leaving him just three tenths of a percent shy of winning the governorship outright.[26]

With the second round underway, Flores focused his efforts on solidifying his support in the provinces, enlisting the help of the MAS's newly elected mayors to serve as his campaign managers in their respective municipalities.[27][28] According to analysts, Flores's main challenge was surviving the vote in the capital, where a majority of the electorate had not voted for either of the top two contenders.[29] For columnist José Luis Quiroga, Flores's chances of winning relied on whether or not voters in the city of La Paz switched their support to his challenger, Santos Quispe, or opted instead to sit out the runoff.[30] Ultimately, a majority of votes broke for Quispe, who defeated Flores by a margin of 55.23 percent to Flores's 44.77.[31]

Food Production Support Enterprise

[edit]Just over a month after his gubernatorial defeat, Flores was appointed to serve as general manager of the state-owned Food Production Support Enterprise (EMAPA).[32] Flores's designation faced pushback from agricultural producers, who criticized his lack of experience in the sector. Speaking to Bloomberg Línea, Luis Fernando Chávez stated that "EMAPA should be managed by a food engineer, by an agronomist, by some experienced agricultural leader, but not by a politician who has never known ... [how to] guarantee food production". Chávez considered Flores's designation to have been the product of political favoritism.[33]

A year into his term, Flores's administration faced protests from producers in Santa Cruz's Integrated North region, who denounced that EMAPA was illegally transporting and storing transgenic corn. Save for soybeans, the use of genetically modified seeds is strictly prohibited by Bolivian law, a regulation producers in the region had for years requested be repealed so as to increase crop yields and ward off pests. The government, however, had historically refused, considering transgenics unsuitable for human consumption and harmful to the environment. As such, when complaints arose that EMAPA had been transporting and storing genetically modified corn, local producers protested the lack of equal enforcement of the law.[34][35] "Here, if someone dares to produce transgenic corn, they threaten us with prosecutors and with taking our land, but for those over there on the border, there is no control", complained Eliazer Arellano, leader of the North Group Producers Association.[36]

In July, disgruntled producers blockaded the highway connecting Montero to San Pedro, where access to EMAPA's storage silos was also blocked off. There, local farmers carried out tests on corn samples taken from ten different transport vehicles, alleging that they had all come out positive as transgenic.[37] On the fifteenth, Flores and other ruling party officials met with Arellano and representatives of the National Association of Oilseed Producers to negotiate an agreement. The five-point deal saw producers end their blockades while EMAPA pledged to take action against the illegal importation of transgenic seeds, among other concessions.[38] However, the agreement fell through within the day, with Arellano accusing Flores of having "escaped" along with the transport trucks, contravening EMAPA's promise to allow producers to carry out a final sampling of the questioned corn. Five days later, Flores announced that EMAPA had completed its own examination, assuring that all observed produce had tested negative for transgenics. Arellano, in turn, accused Flores of being an "incapable manager" and demanded his resignation.[39][40]

Electoral history

[edit]| Year | Office | Party | First round | Second round | Result | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | P. | Votes | % | P. | ||||||

| 2010 | Councillor | Movement for Socialism | 2,670 | 41.19% | 1st | None | Won | [41][γ] | |||

| 2014 | Deputy | Movement for Socialism | 53,534 | 84.60% | 1st | None | Won | [42] | |||

| 2021 | Governor | Movement for Socialism | 618,221 | 39.70% | 1st | 674,220 | 44.77% | 2nd | Lost | [43] | |

| Source: Plurinational Electoral Organ | Electoral Atlas | |||||||||||

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Redistribution; circumscription 21.

- ^ In Bolivia, a second round is avoided by one candidate either reaching fifty percent of the vote or achieving a plurality with ten percent more votes than the next closest competitor.[23]

- ^ Presented on an electoral list. The data shown represents the share of the vote the entire party/alliance received in that constituency.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b "El elegido por Evo y el heredero de El Mallku, en duelo final por la Gobernación paceña". Página Siete (in Spanish). La Paz. 4 April 2021. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ a b Iriarte, Nathalie (20 July 2022). "Bolivia: La alimentación a cargo de un abogado sin registro que no sabe de agro". Bloomberg Línea (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d Romero Ballivián 2018, p. 229.

- ^ "Denuncian que un candidato chocó vehículo de una alcaldía". ERBOL (in Spanish). La Paz. 1 September 2014. Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Atlas Electoral de Bolivia (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. IV (1st ed.). La Paz: Plurinational Electoral Organ. 2016. p. 64. ISBN 978-99905-928-5-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Entre gritos e insultos, queda aceptada la renuncia de Evo Morales". Última Hora (in Spanish). Palma. EFE. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Sánchez, César (21 January 2020). "Diputado del MAS impugnará la decisión de la ALP de aceptar la renuncia de Evo". Oxígeno (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Aguilar se disculpa por polémico impasse con Flores". Correo del Sur (in Spanish). Sucre. ERBOL. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "¿Por qué el senador Aguilar cuestionó al diputado Flores por la muerte de Illanes?". Correo del Sur (in Spanish). Sucre. 27 January 2020. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "La Cámara de Diputados conformó sus 12 Comisiones y 37 Comités: Gestión Legislativa 2015–2016". diputados.bo (in Spanish). La Paz: Chamber of Deputies. 29 January 2015. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Chamber of Deputies [@Diputados_Bol] (27 January 2016). "La Cámara de Diputados conformó sus 12 Comisiones y 37 Comités: Gestión Legislativa 2016–2017" (Tweet) (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Chamber of Deputies [@Diputados_Bol] (31 January 2017). "La Cámara de Diputados conformó sus 12 Comisiones y 37 Comités: Gestión Legislativa 2017–2018" (Tweet) (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "La Cámara de Diputados conformó sus 12 Comisiones y 37 Comités: Gestión Legislativa 2018–2019". diputados.bo (in Spanish). La Paz: Chamber of Deputies. 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "La Cámara de Diputados conformó sus 12 Comisiones y 37 Comités: Gestión Legislativa 2019–2020". diptuados.bo (in Spanish). La Paz: Chamber of Deputies. 24 January 2019. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "En Ayo Ayo proponen al exdiputado Franklin Flores del MAS candidato a Gobernador de La Paz". ERBOL (in Spanish). La Paz. 15 November 2020. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ Peralta, Pablo (15 November 2020). "El Mallku, Quispe y Flores se perfilan para la Gobernación". Página Siete (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ Mamani Cayo, Yolanda (28 November 2020). "MAS suma seis precandidatos con miras a Alcaldía de La Paz". Página Siete (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "Evo: Flores será candidato a la Gobernación de La Paz y Dockweiler a la alcaldía". Urgente.bo (in Spanish). La Paz. 14 December 2020. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "MAS elige a Franklin Flores como candidato a la Gobernación de La Paz". Urgente.bo (in Spanish). La Paz. 27 December 2020. Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "MAS: Interculturales tienen su candidato a gobernador paceño y piden a Evo convocar para definir". ERBOL (in Spanish). La Paz. 23 December 2020. Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Estremadoiro Flores, Ernesto (24 January 2021). "El fallecido 'Mallku' primero en la intención de voto en La Paz, el MAS en Cochabamba y Creemos en Santa Cruz". El Deber (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "Encuesta: Franklin Flores sube en La Paz y el segundo lugar está casi empatado". UNITEL (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Franklin Flores gana en primera vuelta la Gobernación de La Paz, pero habría balotaje". El País (in Spanish). Tarija. 7 March 2021. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "Conteo rápido: Franklin Flores sería el nuevo Gobernador de La Paz". Red UNO (in Spanish). La Paz. 8 March 2021. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "Flores se declara ganador y dice que trabajará con 'hechos y no con palabras'". Página Siete (in Spanish). La Paz. 7 March 2021. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "A Franklin Flores le faltó décimas e irá a segunda vuelta con Santos Quispe". ERBOL (in Spanish). La Paz. 14 March 2021. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Aramayo, Viviana (5 April 2021). "Franklin Flores busca últimos votos en provincias y Santos Quispe en la zona Sur". La Octava (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "Franklin Flores anuncia que los alcaldes electos del MAS serán sus jefes de campaña para la segunda vuelta por la Gobernación de La Paz". La Patria (in Spanish). Oruro. 2 April 2021. Archived from the original on 2 April 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "Segunda vuelta: ¿Cuáles son los escenarios posibles en las cuatro gobernaciones en juego?". Correo del Sur (in Spanish). Sucre. 5 April 2021. Archived from the original on 21 June 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Quiroga, José Luis (7 April 2021). "Entre contradicciones y soberbia". Agencia Boliviana de Información (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "La Paz completa el cómputo en segunda vuelta: Santos Quispe vence en la gobernación y el MAS en la Asamblea". El Deber (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. 26 April 2021. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ "El excandidato a gobernador de La Paz, Franklin Flores, asume la gerencia de Emapa". Correo del Sur (in Spanish). Sucre. Agencia Boliviana de Información. 26 May 2021. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Iriarte, Nathalie (20 July 2022). "Bolivia: La alimentación a cargo de un abogado sin registro que no sabe de agro". Bloomberg Línea (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

'EMAPA debería estar manejada por un ingeniero de alimentos, por un agrónomo, algún dirigente del mismo agro con experiencia, pero no por un político que jamás ha sabido ... ni [como] garantizar la producción de alimentos', dijo Luis Fernando Chávez, productor de girasol y soya de la región del Chaco boliviano.

- ^ Iriarte, Nathalie (19 July 2022). "¿Cómo es que el contrabando está salvando el déficit de maíz en Bolivia?". Bloomberg Línea. Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Estremadoiro Flores, Ernesto (15 July 2022). "El Gobierno investigará el acopio de maíz transgénico en silos de Emapa". El Deber (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Estremadoiro Flores, Ernesto (14 July 2022). "Productores bloquean carretera a San Pedro y denuncian que Emapa acopia maíz transgénico". El Deber (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

'Acá si alguien se atreve a producir maíz transgénico nos amenazan con fiscales y con revertir nuestra tierra, pero para los de allá en la frontera no hay control', se quejó Eliazer Arellano, dirigente del sector.

- ^ "Productores denuncian ingreso de maíz transgénico a Emapa". El Mundo (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. 15 July 2022. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Vásquez, Walter (15 July 2022). "El bloqueo en San Pedro se levanta tras alcanzar un acuerdo de cinco puntos". El Deber (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Vásquez, Walter (15 July 2022). "Productores del Norte Integrado rompen el diálogo con el Gobierno y piden la renuncia del gerente de Emapa". El Deber (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Estremadoiro Flores, Ernesto (20 July 2022). "Después de vaciar sus silos, Emapa realiza su propio test y asegura que no acopió maíz genéticamente modificado". El Deber (in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "Elecciones Municipales 2010 | Atlas Electoral". atlaselectoral.oep.org.bo (in Spanish). La Paz: Plurinational Electoral Organ. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Elecciones Generales 2014 | Atlas Electoral". atlaselectoral.oep.org.bo (in Spanish). La Paz: Plurinational Electoral Organ. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Elección de Gobernadores 2021 | Atlas Electoral". atlaselectoral.oep.org.bo (in Spanish). La Paz: Plurinational Electoral Organ. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)- "Elección de Gobernadores 2021 (Segunda Vuelta) | Atlas Electoral". atlaselectoral.oep.org.bo (in Spanish). La Paz: Plurinational Electoral Organ. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Elección de Gobernadores 2021 (Segunda Vuelta) | Atlas Electoral". atlaselectoral.oep.org.bo (in Spanish). La Paz: Plurinational Electoral Organ. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Romero Ballivián, Salvador (2018). Quiroga Velasco, Camilo Sergio (ed.). Diccionario Biográfico de Parlamentarios 1979–2019 (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). La Paz: Fundación de Apoyo al Parlamento y la Participación Ciudadana; Fundación Konrad Adenauer. p. 229. ISBN 978-99974-0-021-5. OCLC 1050945993 – via ResearchGate.

External links

[edit]- Parliamentary profile Office of the Vice President (in Spanish).

- Parliamentary profile Chamber of Deputies (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 27 June 2020.

- 1979 births

- Living people

- 21st-century Bolivian politicians

- Aymara politicians

- Bolivian municipal councillors

- Bolivian people of Aymara descent

- Bolivian politicians of indigenous peoples descent

- Bolivian trade unionists

- Higher University of San Andrés alumni

- Luis Arce administration personnel

- Members of the Bolivian Chamber of Deputies from La Paz

- Movimiento al Socialismo politicians

- People from Aroma Province